contact:

diann@diannblakely.com

Visit us on Facebook

Site Copyright 2014

All Rights Reserved

020414

THEY’RE NOT DEAD, THEY’RE JUST NOT HERE

AIN'T GOT LONG TO STAY HERE

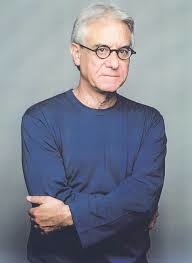

by Stanley Booth

Like the little boy in The Sixth Sense, I see dead people. Everywhere. My wife is in love with a dead man and still flies into rages about a purloined cat, probably passed away too. And my mother killed my father.

Here, a roll call of the deceased, such as Walter Cronkite nightly announced on his news broadcasts during the Vietnam War, might be appropriate, but for the moment, perhaps it’s easier to say that death has mewed behind my footsteps since I was a child. Or written its name on the wall: was it a regional postbellum practice to have sepia photographs taken of newborns, usually wearing what I later learned was called christening attire, who succumbed after only a few months on this planet?

I don’t know, but they seemed a familiar domestic fixture and usually hung in spare bedrooms. “Why do I always have to sleep with the dead baby?” I remember asking on yet another visit to yet another relative. I was further confused by the inherent gender issue: “Why do they all wear skirts? Are they all girls?”

I don’t know, but they seemed a familiar domestic fixture and usually hung in spare bedrooms. “Why do I always have to sleep with the dead baby?” I remember asking on yet another visit to yet another relative. I was further confused by the inherent gender issue: “Why do they all wear skirts? Are they all girls?”

My great-grandmother complicated things even more. Obviously a girl at one time, she didn’t die until I was thirteen, and by then she seemed older than God—especially because she, too, dressed habitually in robes. Granny lived on a vast country plantation and would buy anything sold from a car. City or country, it pays to be a smart shopper, except when it comes to cure-alls, and even then she doubtless finagled a discount. Her death was followed by her son’s—my famously lazy great-uncle Bunyan, the family’s Biblical scholar and collector of the Saturday Evening Post from time immemorial. “Bunyan knows the Bible,” Granny would say. “But Bunyan don’t live the Bible.” No one knows how he died, except that he was found in a chair, his body partially devoured by fire ants.

More details, and fairly interesting ones, surround my father’s demise, which was caused by my mother. She called on the last Thursday night in June 2005. Diann, my wife, answered the phone, listened without speaking for about a minute, and handed the receiver to me. I heard my mother’s voice. “Darling?” she purred. “I want to ask you something.”

My heart sank. Whatever was coming would be, I was certain, tzuris, trouble.

“There’s a man in the bedroom, and he says he’s Stanley Booth.”

Using the three words Col. Parker considered the most important in the language, I said, “Wait a minute.”

Using the three words Col. Parker considered the most important in the language, I said, “Wait a minute.”

“He says he’s either you or Daddy, but I’ve never seen him before in my life. And Daddy’s gone, and he’s been gone for a couple of days. But both of the cars are here.”

My father was eighty-eight, my mother a year younger. For the better part of twelve months, my mother had been saying that my father had Alzheimer’s disease, and their doctor agreed, though he said the condition was only incipient. My mother, I learned too late, had senile dementia. My father had what he called “the wobblies,” and I’d brought him a walker, which enabled him to creep around the house. But my mother said he’d disappeared, wandered off somewhere, and I knew, given his physical state, that was impossible.

During the evening before she called, I’d had most of a bottle of Pinot Grigio. Nothing ever frightened me so badly as what she told me. Suddenly nauseated, I lay down on the floor and felt every last one of my pores open. All at once my body and clothes were soaking wet.

“Call Ernest,” said Diann. Ernest Gilbert, our attorney, the man who presided at our wedding and to whom we refer as “His Holiness,” suggested that we dial 911 immediately. We hadn’t done so in the first place because we had no idea what to say. “Help! My mother’s brain has fallen out and she can’t pick it up!” hardly seemed appropriate. “Give them your parents’ address,” Ernest advised patiently, “and tell them there’s been an emergency there.”

This seemed a wise course of action. Within twenty minutes, we met a full squad of personnel, along with various vehicles and their flashing lights, in my parents’ driveway. Strangely, one of the policemen present was an amateur magician whom I’d known since, years before, my daughter and I had met him at a demonstration he’d given for guests of the local library. Having someone there I knew, especially a magician who could have pulled a cat out of a hat, made the ordeal easier.

This seemed a wise course of action. Within twenty minutes, we met a full squad of personnel, along with various vehicles and their flashing lights, in my parents’ driveway. Strangely, one of the policemen present was an amateur magician whom I’d known since, years before, my daughter and I had met him at a demonstration he’d given for guests of the local library. Having someone there I knew, especially a magician who could have pulled a cat out of a hat, made the ordeal easier.

My father wasn’t dead (yet) but he lasted less than a week. My mother had given him a pillow and a blanket on the floor and left him there for seventy-two hours, the same span of time he was allowed to stay in the hospital. Summarily ejected despite the muscles that were “crushed” (I’m using the medical term) during his ordeal, he couldn’t walk or do much else, but we were most grateful that his physician secured a bed for him in the nursing wing of the best local assisted living facility. We thought it obvious that my mother should join him there in the non-acute section, which offered the equivalent of small apartments. No pets allowed.

For at least two years, Diann and I had made post-Mass, Saturday evening visits to their enormous Mediterranean-style home, and my parents were either to be found in the bedroom, watching the Weather Channel, or in the small nook off the kitchen, eating Raisin Bran. Diann was puzzled by the contrast between these paltry meals and the well-stocked, double-wide pantry, and I explained that it was an indication of my parents’ upbringing during the Depression, akin to my father’s ability to tell you, at any time of any day, the precise amount in his various bank accounts.

Can after can of tuna, soup, vegetables, plus multiple packets of freeze-dried noodles flavored to taste like alfredo or something similar—nothing ever seemed to have been taken out of the larder and cooked. Its floor was notable because of its overflowing bowl of Meow Mix and water for the aforementioned kitty, which Diann believed was insultingly named “Angel.” “Cats are the familiar of choice for witches!” she’d hiss after some visits.

Can after can of tuna, soup, vegetables, plus multiple packets of freeze-dried noodles flavored to taste like alfredo or something similar—nothing ever seemed to have been taken out of the larder and cooked. Its floor was notable because of its overflowing bowl of Meow Mix and water for the aforementioned kitty, which Diann believed was insultingly named “Angel.” “Cats are the familiar of choice for witches!” she’d hiss after some visits.

If born of questionable coupling and christened with Methodist sentimentality, “Angel” was, in fact, befitting. We were to inherit the sweet-natured tabby, but things changed. My parents didn’t trust lawyers and thus used their accountant for all of their financial and legal dealings, and we suspect that his secretary, later instructed to visit my mother every day, was granted kitty-custody by right-of-possession, as I think it’s called. Diann harangued the accountant, and when that didn’t work, she deployed her most threatening tones to harangue me: “That poor feline needs rescue. No respectable cat deserves to be named ‘Angel.’ I’ve explained this before and now it’s time for you to claim her. Exert filial privilege, and as soon as she’s safely in this house, we’ll hold a ceremony and I’ll re-christen her ‘Charon.’ Take the MacNeice line—‘if you want to die, you will have to pay for it’—and throw it straight at that stupid accountant. Surely this will scare him into helpless surrender.”

“Helpless”? What was I? One dead parent, another demented one, and now a wife with a severe case of kitty-lust and in a state of fury I associate with Euripides. “We’d both be dragged into custody after any such venture. Honey, this is south Georgia, not New York or Cambridge [two of  her former places of residence], and no one has ever heard of MacNeice, Charon, or read a poem since forced in high school. Even admitting we’re married is potentially hazardous. Please be reasonable and remember that I know how to pass for ‘normal’ Down Here. You don’t. So let me handle things.”

her former places of residence], and no one has ever heard of MacNeice, Charon, or read a poem since forced in high school. Even admitting we’re married is potentially hazardous. Please be reasonable and remember that I know how to pass for ‘normal’ Down Here. You don’t. So let me handle things.”

This silenced Diann’s frightening hisses, but we don’t know Angel’s fate because of the accountant’s secrecy, preceded by my mother’s reaction to my suggestion that living alone was unsafe for her. I’d already been instructed by my father on his deathbed to return to the house and take the shotguns there home with us. “Your mother,” he said, “is ultra-confused.” This, of course, we knew, and perhaps most definitely when we left to follow the ambulance that took him to the hospital on that humid midnight. “It’s dark,” she said, following us outside. I grasped her hand and, after we moved toward one of the driveway’s lanterns, showed her my watch. “I thought it was nine in the morning,” she responded, a note of suspicion in her voice.

Diann sat with her while I waited with my father for the EMTs to arrive. She later told me that my mother kept pushing her red wallet between the cushion and the side of the chair in which she was sitting. Diann asked why she hadn’t called on any friends for help. “Sometimes people will pretend to be your friends just to get your money,” she whispered nervously, echoing something my father had said at some point about doctors.

As indicated, within a week of hospitalization, then transferral to a nursing home, my father died. His doctor told us that six months previously he had advised both of them to enter an assisted living facility. “They had the good sense never to come back,” he advised us. In fact, we learned that they had stopped going to their cardiac rehab program, church, everywhere except to the grocery store and my mother’s beauty parlor. Each time we visited their house, the same scenario: my parents, the Weather Channel or the Raisin Bran, and Angel. Cats, being naturally neat, don’t like messes. Angel did the best she could to remedy the one she inadvertently made each time she ate. Thank God the water bowl was filled only to a manageable level; otherwise, she would have drowned or died of dehydration, assuring her an early but definite place on this list.

Each time we visited their house, the same scenario: my parents, the Weather Channel or the Raisin Bran, and Angel. Cats, being naturally neat, don’t like messes. Angel did the best she could to remedy the one she inadvertently made each time she ate. Thank God the water bowl was filled only to a manageable level; otherwise, she would have drowned or died of dehydration, assuring her an early but definite place on this list.

Yet I took my mother food several times after my father died. She remained as resistant to the idea of assisted living as she had when my father was alive. She didn’t want, she said, to leave her “nice things.” All of which were covered with dust. As in ashes to ashes, dust to . . .

But again, things changed, and drastically for the worse. My daughter, from whom I have long been alienated, came into town and assured my mother that I was after her money. They assured everyone within earshot of this too, and we were banned from the funeral. But that was okay. My father hadn’t wanted to come to our wedding in 2005, either, because it was hot, and he and my mother often got lost. When I called during the years before their respective demises, she would often recount journeys to places such as Wal-Mart. “Daddy took a wrong turn,” she often pronounced. “You know he has Alzheimer’s.” Then she would turn to my father and ask him where they had been headed.

Here’s a further sampling from my own chain of names: Dewey Phillips (who played the first Elvis Presley record eleven times in a row), Brian Jones, Otis Redding, Gram Parsons, Charlie Freeman, Mike Makris, Mike Alexander, Miss Frances Markert, Jimi Hendrix, Dumar Jardine, Shawn Miller, Ian Stewart, Joe Newton, Walter Smith, Isaac Hayes, Shelby Foote, various aunts, uncles and classmates, one of the few nurses who treated me like a human being when I was hospitalized after breaking my back again, and Jerry Wexler, the record producer for Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and also my surrogate father. As of this writing, what we grimly call the Blakely-Booth Household Body Count has reached sixty-seven in three years and includes many others, eighteen by suicide. A duo of Diann’s belovèds remains Larry Brown and Barry Hannah, the latter dying, like Jim Dickinson—not to mention the former poetry editor of the Oxford American, Jimmy Pitts—of massive coronaries at unexpectedly early ages. Pinetop Perkins, Hubert Sumlin, Honeyboy Edwards—whom Diann once met, and said her small white hand disappeared into what looked like an enormous, and enormously gentle, black paw; an electric shock went up her arm, she further reports, when she realized that this was probably the same hand that last touched Robert Johnson’s.

Here’s a further sampling from my own chain of names: Dewey Phillips (who played the first Elvis Presley record eleven times in a row), Brian Jones, Otis Redding, Gram Parsons, Charlie Freeman, Mike Makris, Mike Alexander, Miss Frances Markert, Jimi Hendrix, Dumar Jardine, Shawn Miller, Ian Stewart, Joe Newton, Walter Smith, Isaac Hayes, Shelby Foote, various aunts, uncles and classmates, one of the few nurses who treated me like a human being when I was hospitalized after breaking my back again, and Jerry Wexler, the record producer for Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, and also my surrogate father. As of this writing, what we grimly call the Blakely-Booth Household Body Count has reached sixty-seven in three years and includes many others, eighteen by suicide. A duo of Diann’s belovèds remains Larry Brown and Barry Hannah, the latter dying, like Jim Dickinson—not to mention the former poetry editor of the Oxford American, Jimmy Pitts—of massive coronaries at unexpectedly early ages. Pinetop Perkins, Hubert Sumlin, Honeyboy Edwards—whom Diann once met, and said her small white hand disappeared into what looked like an enormous, and enormously gentle, black paw; an electric shock went up her arm, she further reports, when she realized that this was probably the same hand that last touched Robert Johnson’s.

Barry and Alex Chilton—whom I’d known perhaps a little too well in his Memphis days and had to eject forcibly from my home several times before he reached twenty-one—died days apart from each other. Between the double parentheses that constitute “the facts, ma’am, just the facts,” Diann lost her best friends from high school and college, but neither had remained in close touch, as she had with Larry and Barry, and as regards Alex, you’ll have to read her part of this essay. For the moment, all I can reveal is that she sat for two weeks at the kitchen table, fingering and trying to re-read letters from Larry and Barry without much success. Fierce she may be, but when those she loves suddenly disappear from the planet, she weeps and weeps for days on end, lights candles, murmurs Voodoo Episcopalian prayers . . . and then, on 30 December 2011, Eleanor Ross Taylor died.  The two had been very close, but in the case of “Mrs. Taylor,” Diann deflected her mourning into a campaign, wanting to ensure that Mrs. Taylor would not be forgotten, and though as worried about his spouse as any husband would be when she insisted on staying awake for thirty-six hours straight to contact various friends and others within that precious circle, once again she wouldn’t be stopped.

The two had been very close, but in the case of “Mrs. Taylor,” Diann deflected her mourning into a campaign, wanting to ensure that Mrs. Taylor would not be forgotten, and though as worried about his spouse as any husband would be when she insisted on staying awake for thirty-six hours straight to contact various friends and others within that precious circle, once again she wouldn’t be stopped.

Attempting to maintain chronology at this point seems superfluous. Jimmy Pitts’s widow retains a Facebook page for fans of his music. He once asked Diann’s assistance in creating a selection of new and older poems, and me to listen to a début CD for a scuttled collaborative “Night Table” column we intended to use as a mean of highlighting recent books, DVDs, and music . . . when did he leave us? What’s the use of looking up dates at this point? I can say only that now Levon Helm, Douglas “Duck” Dunn, Doc Watson, Sid Selvidge, and Jerry McGill are the most recent additions to that roll call.

But I get ahead of myself: Jerry died on August 15th, 2008 at the age of ninety-one, and not quite a year later, my own best friend from Memphis State, Jim, the record producer, had two heart attacks and a triple bypass, during which he died and was revived four times. Then he died again, like Jerry, on August 15th at Methodist Hospital in Memphis: his great heart, sealed in 300+ pounds of walking barbeque, simply quit beating. Eerily enough, he died one year to the day after Jerry.  “Dylan, the Stones . . . I’ve had a good run, haven’t I?” Jim said in our last phone conversation. (For his exchanges with Diann, see her half of this saga.) All of which proves my point, sadly enough, though she has said that my skull ring, so attractive to a famous friend that he had a duplicate made, gives her the creeps. “We’ve got an entire box of hospital records in the laundry room and need no further memento mori around this house,” she emphatically avers, adding that we attract death like white on grits. (In my parents’ house, of course, they would have been spilled on the floor too.)

“Dylan, the Stones . . . I’ve had a good run, haven’t I?” Jim said in our last phone conversation. (For his exchanges with Diann, see her half of this saga.) All of which proves my point, sadly enough, though she has said that my skull ring, so attractive to a famous friend that he had a duplicate made, gives her the creeps. “We’ve got an entire box of hospital records in the laundry room and need no further memento mori around this house,” she emphatically avers, adding that we attract death like white on grits. (In my parents’ house, of course, they would have been spilled on the floor too.)

The worst such occurrence wasn’t actually a death but a near-miss—or near-hit—on December 30th, 2007. In the hospital for a month with a bad case of bronchitis, Diann was awaiting her discharge papers when she had a still-unexplained seizure. Her records state “polypharmaceutical toxicity” as the cause, meaning that the various specialists who came and went during those weeks, deleting one drug from her regimen and substituting another, in effect poisoned her, and she went into respiratory arrest. Rushed on a gurney to the ICU, she remained there for another month with a ventilator tube jammed down her throat and a similar device in her nose for feeding her liquid protein. “What are her chances?” I asked Diann’s pulmonologist, who had stabilized her precarious lungs once before, thus saving her life. “50%. Or, to be fair, given the underlying condition, 25%.”

This was not interesting, or even an occasion for sorrow. This was honesty, and it terrified me. But though unable to save either parent, I proved more capable here, if only through a combination of accident and absent-mindedness: I neglected to bring the portable liquid oxygen tank—it’s actually quite small— we’d acquired when she first fell ill, and the hospital refused to give us another for “transport [home]”; otherwise, she would have had the seizure in the car and died. Of course, I had assistance from Dr. Colman Sudduth’s diligent and devoted efforts, as well as from the staff of the long-term care facility in Green Cove Springs, Florida, whose name seemed as strange as Angel’s: “Kindred.” Yes, as in “spirits,” though the place’s intention is to minister to the flesh. Located in a bedroom community of Jacksonville, Green Cove Springs is home to a number of Katrina survivors and Caribbean families who were on the way to what Diann believes is her soul’s true home—one of them, anyway—New Orleans, when the hurricane made landfall, followed by the man-made disaster of even worse proportions.

we’d acquired when she first fell ill, and the hospital refused to give us another for “transport [home]”; otherwise, she would have had the seizure in the car and died. Of course, I had assistance from Dr. Colman Sudduth’s diligent and devoted efforts, as well as from the staff of the long-term care facility in Green Cove Springs, Florida, whose name seemed as strange as Angel’s: “Kindred.” Yes, as in “spirits,” though the place’s intention is to minister to the flesh. Located in a bedroom community of Jacksonville, Green Cove Springs is home to a number of Katrina survivors and Caribbean families who were on the way to what Diann believes is her soul’s true home—one of them, anyway—New Orleans, when the hurricane made landfall, followed by the man-made disaster of even worse proportions.

But she, too, survived, and learned to hold a fork, dial a phone, and walk again. She, unlike Jim, who was a couple of months older than me, remains on this side of the grass, as we say in the South. For the moment. Yet Jim asked that his tombstone be inscribed with the following: “I’m not dead; I’m just not here.” Or, as Jimi put the matter in “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “If I don’t see you no more in this world / I’ll see you in the next one / And don’t be late.” Which suggests that hope remains for us all. And that we should keep an eye on the clock.

But she, too, survived, and learned to hold a fork, dial a phone, and walk again. She, unlike Jim, who was a couple of months older than me, remains on this side of the grass, as we say in the South. For the moment. Yet Jim asked that his tombstone be inscribed with the following: “I’m not dead; I’m just not here.” Or, as Jimi put the matter in “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “If I don’t see you no more in this world / I’ll see you in the next one / And don’t be late.” Which suggests that hope remains for us all. And that we should keep an eye on the clock.

TRIBAL MARKINGS

by Diann Blakely

When Dylan accepted his three Grammys for Time Out of Mind, he not only thanked Jim, the album’s keyboardist, but also called him “my brother.” Jim’s talents in this arena and as a producer made him legendary, though to most his fame is restricted to having played the piano on a 5:41 Rolling Stones song called “Wild Horses.” You might say that we first met there. Less than two decades later, Jim growled his way into my house, ears, and heart with “Down in Mississippi,” a track on one of the Oxford American’s stellar annual compilation discs. Jim chose his company as carefully as Dylan, Keith, and Stanley, and on the 1997 Southern Sampler he joins forces with Skip James, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Carl Perkins, the Meters, Phineas Newborn, Jr., and, also, Lucinda Williams in “Pineola,” her dirge for Frank Stanford, the suicide whose poems retain an ur-Southern surrealistic landscape of levees and battlefields.

All of these singers would play a part in my life and/or Stanley’s, whom I didn’t meet until 2002, almost a year after a review I had published, one that included a special focus on the newly released editions of his two best-known books, made its way into his hands. In our first months as a couple, Stanley himself was asked to write about a new biography of a blues great; his mood was so vicious it scared me. Just the other day, I came across a notebook scarred by the following phrase: “If this book weren’t about Muddy Waters, I’d shoot a hole through it.” He was happier when asked to write the liner notes for the new release of Dixie Fried.

Jim serves as a pinnacle—though he would probably prefer the image of a gigantic circus tent—in the history of American vernacular music, though this second image comes from Furry Lewis, who averred that the circus would never be unbroken. Furthermore, Jim deserves the highest praise that Keith Richards once said could serve as epitaph for bluesmen (and women): “He passed it on.” Some day there will be a plaque marking where his two trailers stood in Mississippi, one in which he and Mary Lindsay lived and raised Cody and Luther, a/k/a “The North Mississippi Allstars” et alia, and the other which Jim used as a studio. “Zebra Ranch” it should read, as the home from which Jim practiced and preached his truest gospel: “World boogie is coming!” Perhaps Keith’s words could serve as a P.S.

Jim met the man who would become my husband at Memphis State. Because Keith would re-enter their lives when Stanley called Jim from Muscle Shoals to see if he’d like to play some piano, it’s hard for me not to think of another meeting, a more famous one: a Dartford train platform, an adolescently scrawny pair of former schoolmates, the young Mr. Richards spotting Mick with an armful of albums by Messrs. Waters and Berry.

This dual tribute to Jim contains many pairs and pairings. And it contains two falls, or twice that if you count the mental collapse of Stanley’s mother and the term for a hurricane’s assault on land. My tumble occurred several years after Stanley’s father’s atop his own bedroom carpet: as the day of Jim’s passing pivoted into the morning of August 16th—which Jim, too, would have naturally remembered first as the date of Robert Johnson’s death, and then only later as The King’s—I went into the bathroom, where my supposedly skid-proof mat scrunched beneath my toes. I hit the side of the tub with the force of opposing SEC linebackers, each about Jim’s size, meeting in a monstrous pair at the fifty-yard line.

There are also two felines: Jim’s favorite film is a series of strange scenarios titled Track of the Cat. While I didn’t understand the tracking shots or anything else, I thought it a kindly gesture to type an email to relay that we were watching the movie, sprawled on the bed one Sunday afternoon. Jim replied with an incomprehensible line from the script, “Black painter, whole world.” An esoteric synonym for “panther,” I learned: had both the screenwriter and Jim somehow predicted my determination to rename Angel? Wouldn’t surprise me: Jim was nothing if not magic.

I have been working for fifteen years on a manuscript of poems titled Rain in Our Door: Duets with Robert Johnson. Part of the reason it remains unfinished has to do with the multiple moves Stanley and I have made; another is related to the chain of casualties (The B-B Household Body Count, resulting in a series of in memoriam pieces). We have offered full reports to my priest and our psychiatrist, who both stared at us with open mouths, saying they’d never heard of so many lost in such a short time, which neither of us found particularly helpful. Nor was that little incident in 2007 and Stanley’s follow-up success of pulling a drawer out of the kitchen cabinetry and re-breaking his back. But now? A post-elegiac spell has been cast, and we know better than most how to exorcise its powers: a side-by-side effort in the form this essay provides.

I have been working for fifteen years on a manuscript of poems titled Rain in Our Door: Duets with Robert Johnson. Part of the reason it remains unfinished has to do with the multiple moves Stanley and I have made; another is related to the chain of casualties (The B-B Household Body Count, resulting in a series of in memoriam pieces). We have offered full reports to my priest and our psychiatrist, who both stared at us with open mouths, saying they’d never heard of so many lost in such a short time, which neither of us found particularly helpful. Nor was that little incident in 2007 and Stanley’s follow-up success of pulling a drawer out of the kitchen cabinetry and re-breaking his back. But now? A post-elegiac spell has been cast, and we know better than most how to exorcise its powers: a side-by-side effort in the form this essay provides.

An effort that I hope proves more successful than the last time my husband and I joined as co-conspirators: we were fired. William Eggleston has been among my favorite photographers for years before I ever met Stanley, and given the chance to collaborate on an article about For Now, the catalog for Eggleston’s LACMA show, we were initially delighted. Stanley was to write a reminiscence of the man, who is a longtime friend, and I was to write about For Now, which, in addition to the photographs, contains essays and interviews.

An effort that I hope proves more successful than the last time my husband and I joined as co-conspirators: we were fired. William Eggleston has been among my favorite photographers for years before I ever met Stanley, and given the chance to collaborate on an article about For Now, the catalog for Eggleston’s LACMA show, we were initially delighted. Stanley was to write a reminiscence of the man, who is a longtime friend, and I was to write about For Now, which, in addition to the photographs, contains essays and interviews.

Film director Michael Almereyda edited the catalog, and I also wanted to discuss his documentary, William Eggleston in the Real World. I was especially bitten, so to speak, by a quotation Greil Marcus had given me from Almereyda’s vampire flick, Nadja, thinking it would have special appeal for Memphis cognoscenti—like Dylan, like Keith, like Jim, like Stanley, like Eggleston—who also know something about hangers-on. Probably like Peter Fonda, who plays Van Helsing. He compares Dracula to Elvis in his final days: “Drugs, sick, surrounded by flunkies. I didn’t kill him. He was already dead.” Probably surrounded by dead cats.

Fonda doesn’t mention Nixon, though. Like Elvis, Johnson was welcomed to the White House—although in memory and far grander style—when, during Black History Month last year, our President Re-Elect sang a few bars of “Sweet Home Chicago” with B. B. King and Buddy Guy. This evening, devoted to a general celebration of the blues, was held a few months before the possible centennial anniversary of Johnson’s birthday—1911? 1912?—for which sources differ, a point occasioning actual fist-fights at scattered but national convenings of various cultists elsewhere. There are hangers-on and death-groupies, but also ghostly teachers, waiting to whisper their wisdom to us if we will only listen, just the same way surely as the rising sun will, indeed, go down:

Fonda doesn’t mention Nixon, though. Like Elvis, Johnson was welcomed to the White House—although in memory and far grander style—when, during Black History Month last year, our President Re-Elect sang a few bars of “Sweet Home Chicago” with B. B. King and Buddy Guy. This evening, devoted to a general celebration of the blues, was held a few months before the possible centennial anniversary of Johnson’s birthday—1911? 1912?—for which sources differ, a point occasioning actual fist-fights at scattered but national convenings of various cultists elsewhere. There are hangers-on and death-groupies, but also ghostly teachers, waiting to whisper their wisdom to us if we will only listen, just the same way surely as the rising sun will, indeed, go down:

I think that what causes Memphis music to happen is the spirit, it’s not here all the time—it comes and goes—but I think it’ll be back. It’s stronger than what’s down there on Beale Street now, whatever was in the bushes that talked to Robert Johnson is still there. I mean, what happened on Beale Street is cultural genocide but you can still walk down there and feel something—very vaguely but it’s there. I don’t know if it’s in the dirt—Knox Phillips [Sam’s son] says it’s in the water—but it has something to do with humidity, that’s for sure. Maybe it’s a combination of that and the low altitude . . .

You go to Boulder, Colorado and try to make a record—you’re in a lotta fuckin’ trouble—there’s not enough density in the air. If you go to New Orleans, there’s almost too much, you have to understand what you’re dealing with here! Nashville is only two hundred miles away but it’s so different that it might as well be on the other side of the earth. (with Joss Hutton, Perfect Sound Forever, 2002)

Jim’s words are truer than most ever spoken, though the places are somewhat different: Stanley and I fled Nashville, where I lived for fifteen mostly miserable years, for another High Temple of Americana-worship—Kerrville, Texas, humidity-free and supposedly one of the healthiest locales in the country. Jimmie Rodgers went there for his TB, and his house remains. Kinky Friedman was the mayor, and while we feel sure that it was during Friedman’s tenure that the murderous antics of the Baby Killer Nurse were stopped, we never saw him or anything remotely kinky about the place.

Jim’s words are truer than most ever spoken, though the places are somewhat different: Stanley and I fled Nashville, where I lived for fifteen mostly miserable years, for another High Temple of Americana-worship—Kerrville, Texas, humidity-free and supposedly one of the healthiest locales in the country. Jimmie Rodgers went there for his TB, and his house remains. Kinky Friedman was the mayor, and while we feel sure that it was during Friedman’s tenure that the murderous antics of the Baby Killer Nurse were stopped, we never saw him or anything remotely kinky about the place.

In fact, I could scarcely see at all, because, like Johnson, I have cataracts, which can be caused by overexposure to light. The sun’s rays were migraine-inducing, intensified by the air’s lack of moisture; and, coupled with Stanley’s seeming dissolve into Cowboy Land—did he want to stay in Kerrville forever, trapped in fantasies of riding Trigger before that poor animal was taxidermied?—I panicked, if unnecessarily, for though Stanley loathed Kerrville as much as I did in the kind of misunderstanding typical of newlyweds, my greatest concern was that I couldn’t hear Johnson’s voice any longer. Now I’m beginning to hear its echo in my own shrubbery, and I intend to lure him first onto my porch and then to “come on in my kitchen,” for rain threatens always here in south coastal Georgia. In other words, I intend to make him fall back in love with me so that I can finish my book.

Yet I recognize that my vocation, like Jim’s, is dual: I have a longing to serve the Word beyond my own scribblings on the page. Jim served the music of “the old, weird America”—again to quote Marcus, another of its music’s irrefutable spokespersons—in his own rock-and-blues-based recordings, none made too far from those Johnson-haunted bushes. Jim served the Word in the form of Song, and doubly so. He didn’t write lyrics or music himself but channeled the best of the past through that voice that more than growled—indeed, it seemed to start somewhere around his knees—in addition to acting as a discriminating yet tireless supporter of younger artists.

Yet I recognize that my vocation, like Jim’s, is dual: I have a longing to serve the Word beyond my own scribblings on the page. Jim served the music of “the old, weird America”—again to quote Marcus, another of its music’s irrefutable spokespersons—in his own rock-and-blues-based recordings, none made too far from those Johnson-haunted bushes. Jim served the Word in the form of Song, and doubly so. He didn’t write lyrics or music himself but channeled the best of the past through that voice that more than growled—indeed, it seemed to start somewhere around his knees—in addition to acting as a discriminating yet tireless supporter of younger artists.

One of the earliest, Alex Chilton, who died almost exactly eight months after Jim, and also of a massive coronary, owed much to his most faithful and least intrusive studio master. Alex owed Stanley and me an interview. “How about August?” I asked the same summer as Jim’s death. “Well, I tend to evacuate around then,” Alex replied, drolly referring to his forced post-Katrina removal from his longtime home—“bone-dry” might be an appropriate modifier here—in Treme, and our attempts at rescheduling failed. But the duo of Chilton and Dickinson resulted in Like Flies on Sherbet, initially greeted with boos and hisses but now regarded as a masterpiece.

Jim was Alex’s most memorable commentator in the voluminous interviews he gave with such generosity. It was as though he feared too much would be lost if he didn’t continue to support the records he produced, even decades after the fact.

Jim was Alex’s most memorable commentator in the voluminous interviews he gave with such generosity. It was as though he feared too much would be lost if he didn’t continue to support the records he produced, even decades after the fact.

Jim himself had many bands with many names, but my favorite was “Mudboy and the Neutrons,” which survived for one CD, They Walk Among Us. The nom de band? Created, Jim explained, so he could shoot back “That’s Mr. Mudboy to you.” As if foreseeing his own extinction, he titled his solo finale Dinosaurs Run in Circles, which was released slightly more than three months before his death.

Jim’s self-penned epitaph—“I’m not dead. I’m just not here”—was proved right almost immediately. Three days after his spirit passed, Luther assembled Cody, Sid and Steve Selvidge (another father-son duo, with the paternal side of the equation lost just a few months ago), Jimmy Croswait, Paul Taylor, Jimbo Mathus, and Shannon McNally at Zebra Ranch to record Onward and Upward, a CD of the religious standards he loved. The process was finished in another biblical three days, and while the outcome didn’t resuscitate the man in body, its existence, and the Grammy nomination, came close. Luther was also a member of the Black Crowes at this time, and in September he performed a concert with them at the Lyric in nearby Oxford, MS, which was recorded as part of the public TV series Live at the Artists Den and served as a bittersweet homecoming. As the Allstars, Luther and Cody have just released their latest CD, using for its title their father’s constant avowal that World Boogie is Coming.

Jim’s self-penned epitaph—“I’m not dead. I’m just not here”—was proved right almost immediately. Three days after his spirit passed, Luther assembled Cody, Sid and Steve Selvidge (another father-son duo, with the paternal side of the equation lost just a few months ago), Jimmy Croswait, Paul Taylor, Jimbo Mathus, and Shannon McNally at Zebra Ranch to record Onward and Upward, a CD of the religious standards he loved. The process was finished in another biblical three days, and while the outcome didn’t resuscitate the man in body, its existence, and the Grammy nomination, came close. Luther was also a member of the Black Crowes at this time, and in September he performed a concert with them at the Lyric in nearby Oxford, MS, which was recorded as part of the public TV series Live at the Artists Den and served as a bittersweet homecoming. As the Allstars, Luther and Cody have just released their latest CD, using for its title their father’s constant avowal that World Boogie is Coming.

Zebras, presumably like dinosaurs, are undomesticable, yet Jim was as hearth-loving and uxorious as they come. Thus a distinguished handful of younger musicians whose bluesy comings-of-age took place elsewhere but were assisted by his music, naturally took the next step: Voodoo Baptist pilgrimages to the Ranch in hopes of his benefaction and encouragement. The last of whom I’m aware are, fittingly enough, a twosome: the Scissormen, who cut heads indeed, as Jim and I discussed in what turned out to be our final phone conversation. I still have a piece of paper with the duo’s names scribbled on it: “Rob, ‘R.L.,’ Hulsman and Ted Drozdowski,” he said. “Get ’em to send you some CDs.” “Sure, Jim, but would you please spell Ted’s last name again?” I asked. He replied more expansively elsewhere: “Ever wonder what would have happened if Bukka White had discovered the Fuzz Tone? Or if Skip James had played piano with Antenna Jimmy and Drumbo from the Magic Band?” Rhetorical questions, perhaps, but the answer is “acid blues for the 21st century,” or a howling gutbucket mélange of Delta, Hill Country, and Chicago blues.

Zebras, presumably like dinosaurs, are undomesticable, yet Jim was as hearth-loving and uxorious as they come. Thus a distinguished handful of younger musicians whose bluesy comings-of-age took place elsewhere but were assisted by his music, naturally took the next step: Voodoo Baptist pilgrimages to the Ranch in hopes of his benefaction and encouragement. The last of whom I’m aware are, fittingly enough, a twosome: the Scissormen, who cut heads indeed, as Jim and I discussed in what turned out to be our final phone conversation. I still have a piece of paper with the duo’s names scribbled on it: “Rob, ‘R.L.,’ Hulsman and Ted Drozdowski,” he said. “Get ’em to send you some CDs.” “Sure, Jim, but would you please spell Ted’s last name again?” I asked. He replied more expansively elsewhere: “Ever wonder what would have happened if Bukka White had discovered the Fuzz Tone? Or if Skip James had played piano with Antenna Jimmy and Drumbo from the Magic Band?” Rhetorical questions, perhaps, but the answer is “acid blues for the 21st century,” or a howling gutbucket mélange of Delta, Hill Country, and Chicago blues.

The Scissormen are the stars featured in the new Robert Mugge film Big Shoes: Walking and Talking the Blues. If you’re really interested in backstory, Ted works for the same alt-weekly for which I wrote “Getting Respectable,” leading to my e-mail courtship with their author, in its infancy at this point a dozen years ago.

Jump-cut to 2005, when the two of us became one at a wild impromptu betrothal held in His Holiness’s office. “Wild”? The small room which houses the desk and files of Judge Gilbert, a world-class hunter who makes his own bows and arrows, was further crammed with fauna which had met Trigger’s ultimate fate, including a full-size bear.

Jump-cut to 2005, when the two of us became one at a wild impromptu betrothal held in His Holiness’s office. “Wild”? The small room which houses the desk and files of Judge Gilbert, a world-class hunter who makes his own bows and arrows, was further crammed with fauna which had met Trigger’s ultimate fate, including a full-size bear.

Jim would have approved, as he would of my vial of dirt collected from the various sites where Johnson is said to have made his deal with the devil and/or to have been buried. He once told Stanley that “a man can never have too many amulets,” and Lord knows this house is full of ’em. I need my own charms and rituals and dresser- and bathroom-countertop icons—even a cat’s paw, dyed pink, dangling from my key ring—just as surely as my husband. Thus I like to think Jim would have found a double helping of good juju here.

100113 21:42