Site Copyright 2013

All Rights Reserved

090313

DOWN—BUT NOT OUT—

IN MISSISSIPPI AND ELSEWHERE

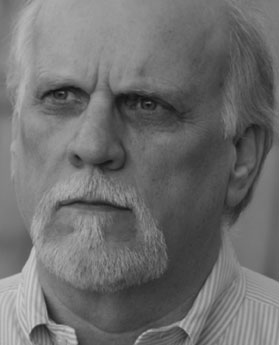

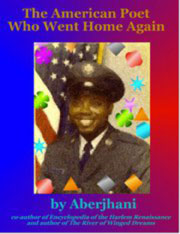

(photo credit: Melanie Young)

Part One: Brother Rick Ain’t Gone

If the rest of the country remains in the hold of an economic recession, the Deep South—post-Katrina, post-BP disaster, post-floods-and-droughts, and post-tornados, for starters—has been so ferociously imperiled by dire economic times that only the Great Depression seems worse. A pandemic of budget cutbacks, coupled with unusually nasty university politics in the case of Frederick Barthelme, ended not only in his 2010 ouster from the helm of the Mississippi Review, but also in Rie Fortenberry’s, the managing editor. She’d held the position since the nationally respected and defiantly nonregional journal’s founding in 1977, the same year Barthelme began the literary/administrative equivalent of CPR on the University of Southern Mississippi’s creative writing program.

Thus the Center for Creative Writing at USM, as it came to be called, was transformed into a nexus for this our sullen craft, etc., one offering the Ph.D. While his brother Steven and Angela Ball remain, Mary Robison left for the University of Florida and Julia Johnson fled to the University of Kentucky. The latter, a native New Orleanian with a God-given talent for speaking her mind, makes the Chronicle of Higher Education’s in-depth coverage of the sad, indeed ludicrously short-sighted, decision of USM’s relatively new president, an agricultural economist, required reading even eighteen months after its publication. What other marks of genuine intellectual distinction did USM have other than those Barthelme and the teaching/editing staff he assembled provided?

But, as indicated by my title, all is not gone. Barthelme hasn’t left his one dear perpetual state—a novel-in-progress—and the “FB’s Greatest Hits” volume of Mississippi Review, comprised of 700 pages and three issues of work, selected by Johnson in her final act as editor. Johnson’s willingness to undertake such a task is yet another index of the profound loyalty Barthelme continues to evoke from those with whom he works, in whatever capacity.

In fact, such devotion would seem to continue from beyond the grave: until the publication of Jean Cash’s new biography of Larry Brown (University Press of Mississippi; and check out also the volume in their splendid Conversations series with Brown), who remembered that Barthelme was not only among  the first to publish a story by the Mississippi sharecropper’s son, but also that the acceptance brought the eponymous work of his début collection, Facing the Music, into view? The conclusion alone makes it easy—or should—to understand why, according to Barthelme, the process of reading “Facing the Music” and placing a congratulatory phone call of acceptance to the author took no more than twenty minutes.

the first to publish a story by the Mississippi sharecropper’s son, but also that the acceptance brought the eponymous work of his début collection, Facing the Music, into view? The conclusion alone makes it easy—or should—to understand why, according to Barthelme, the process of reading “Facing the Music” and placing a congratulatory phone call of acceptance to the author took no more than twenty minutes.

For the rest of the story and its various elements of excellence notwithstanding, the work's final line—“We reach to find each other in the darkness like people who are blind”—exemplifies the great, almost Jamesian empathy that infuses the female characters limned by both Barthelme and Brown, the latter rendering the hurt, self-hatred, and heartbreak of the scarred wife whose mastectomy has extinguished her husband’s desire for her like a double soul-mirror.

Barthelme may have been scarred himself in recent years, but “he don’t bow and he don’t kneel” might well be his credo. Nor has he ever, so to speak, painted himself—despite a stint playing with a band initially called Red Crayola—into a corner with his signature style; even when the corporation we know from childhood issued complaints and legal threats, Barthelme, ever attentive to the smallest components of language, changed the “C” to a “K,” and thus Red Krayola was born and has remained.

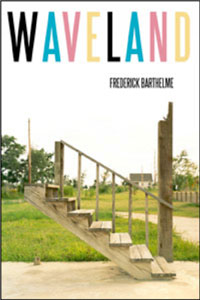

If always unfolding scene by discrete scene, as if in a film, Barthelme’s canon might also be called that of a master director: the means of dramatization changes with each different setting and cast of characters—see Southern Scribe’s “Interview with Frederick Barthelme”—even when using that supposedly non-fictional form we call “memoir,” i.e. Double Down: Reflections on Gambling and Loss, co-authored with his brother Steven and one of the genre’s best in recent years. Then there are—and this is not an all-inclusive list—the three books of short fiction and nine novels that F. Barthelme has written to date, most recently  Waveland (Vintage), which Esquire pronounced “sublime,” praising its author as one who “seems to argue we might still find a separate peace from the terrors of the wider world.” Especially one in which the “natural disaster become man-made catastrophe” becomes, in turn, “the Katrina show.” In his first major work of fiction since Elroy Nights (for an excellent, straightforward, and informative slice of Barthelmiana, check out Fictionaut), that separate peace seems all the more relevant after a series of months during which an earthquake occurred, cracking the Washington Monument and delaying Obama’s dedication of the structure built in remembrance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; Hurricane Irene threatened New York City and environs; a tropical storm wreaked havoc as far north as Maine, with CNN showing caskets being forced from Vermont graves because of the immense subterranean pressure exerted by water; that gruesome slaughter of four dozen “exotic animals” in Ohio; Occupy protestors being beaten, clubbed, and gassed all over the country; and the numbingly continuous “Middle East show.”

Waveland (Vintage), which Esquire pronounced “sublime,” praising its author as one who “seems to argue we might still find a separate peace from the terrors of the wider world.” Especially one in which the “natural disaster become man-made catastrophe” becomes, in turn, “the Katrina show.” In his first major work of fiction since Elroy Nights (for an excellent, straightforward, and informative slice of Barthelmiana, check out Fictionaut), that separate peace seems all the more relevant after a series of months during which an earthquake occurred, cracking the Washington Monument and delaying Obama’s dedication of the structure built in remembrance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; Hurricane Irene threatened New York City and environs; a tropical storm wreaked havoc as far north as Maine, with CNN showing caskets being forced from Vermont graves because of the immense subterranean pressure exerted by water; that gruesome slaughter of four dozen “exotic animals” in Ohio; Occupy protestors being beaten, clubbed, and gassed all over the country; and the numbingly continuous “Middle East show.”

In such times, regional distinctions, if not national ones, seem wildly irrelevant—though Barthelme has admitted his fondness for Mississippi’s Gulf Coast—and the Mississippi Review has always had a country-wide readership and roster of contributors, a pattern that is being continued at Mississippi Review’s new iteration,  Blip Magazine. Its formation proved only to force Barthelme into editorial triple-tasking: attempting to trace various trajectories, I became so confused that I found it necessary to plead, blushingly, for the following paragraph:

Blip Magazine. Its formation proved only to force Barthelme into editorial triple-tasking: attempting to trace various trajectories, I became so confused that I found it necessary to plead, blushingly, for the following paragraph:

I edited the university-sponsored Mississippi Review print magazine from 1977-2010. In 1995 I started an independent online-only magazine called Mississippi Review Online (or MROnline) which was conceived and produced without any support from the university, and did not rely on work from the print edition of Mississippi Review (although it did, occasionally, reprint with permission material from that magazine). MROnline was published 1995-2010 and was made up of about 90-95% original material published solely online. In August of 2010 we morphed MROnline into the current Blip Magazine—(www.blipmagazine.net)—thinking that we’d best draw a clear distinction between the new magazine and the old.

Further detective work revealed some things that Barthelme has to say about “Southern literature” in general and Blip Magazine, Mississippi Review, and Mississippi Review Online in particular:

I actually do not have any big thoughts about the South as a distinct subsection of the country, have long thought that this was, by now, a largely artificial division, perhaps culturally still significant (as Italians are to Danes, so . . .) but mostly just geographical gossip fodder. Yes, the Northeast has more money, and the West has what it has, and Montana etc., Vegas, etc. And we are plagued with the slow-footed, but in some larger sense we’re all in it together, economically and culturally, which is why when we restarted Mississippi Review in 1977 we set out to make a national literary magazine, to participate in the national literary culture, to be invested in the American literature and not so much in Southern Literature. In fact, I don't even much like the idea of Southern Literature, as too much of it relies far too heavily on national  stereotypes, good ol’ boys, Southern cooking, etc. etc. Many have made good successes parading in Southern drag for the Northern Liberal Elite, as you know, and there is always the question of “authenticity,” that is, when is authentic not really authentic any more? Time passes and changes things, the culture is infiltrated and changed and homogenized, and to cling to the prior culture is to pretend that what has happened actually hasn’t happened. This is not to say that in some deep hollows the old ways do not or should not obtain, for they do, whether they should or not, but in most ways most of the Old South is just about like the North or the East or the West. The particulars might be different, but the substance is similar.

stereotypes, good ol’ boys, Southern cooking, etc. etc. Many have made good successes parading in Southern drag for the Northern Liberal Elite, as you know, and there is always the question of “authenticity,” that is, when is authentic not really authentic any more? Time passes and changes things, the culture is infiltrated and changed and homogenized, and to cling to the prior culture is to pretend that what has happened actually hasn’t happened. This is not to say that in some deep hollows the old ways do not or should not obtain, for they do, whether they should or not, but in most ways most of the Old South is just about like the North or the East or the West. The particulars might be different, but the substance is similar.

Barthelme has excited my envy with many phrases, but none to the same level of covetousness as “Southern drag,” surely.

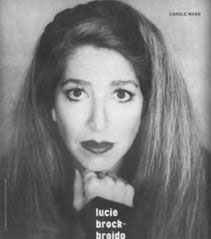

Of greater “substance,” however, is Barthelme’s tech-savvy: not only was he able to create the Blip Magazine site but also to take most of the former publication’s archives with him, a crucial move when one considers what might have been lost. Indeed, a 1997 Atlantic interview about the digital age shows Barthelme to have been genuinely avant-garde. To find some of the best poetry, fiction, and interview features being published in recent years, just check either Blip Magazine or Mississippi Review Online.  There you’ll find contributions by Kate Braverman, Lucie Brock-Broido (whose collected poems have just been published in the UK by Carcanet as a “public service,” and they ain’t just whistlin’ Dixie, an apt phrase when one considers the most recent poem of hers I’ve read, “A Meadow”) Bret Easton Ellis, Mary Gaitskill, Amy Hempel, David Lehman, Rick Moody, and Robert Polito (look for the last at the noir intersection of Hollywood and God, in Memphis, or even Chicago).

There you’ll find contributions by Kate Braverman, Lucie Brock-Broido (whose collected poems have just been published in the UK by Carcanet as a “public service,” and they ain’t just whistlin’ Dixie, an apt phrase when one considers the most recent poem of hers I’ve read, “A Meadow”) Bret Easton Ellis, Mary Gaitskill, Amy Hempel, David Lehman, Rick Moody, and Robert Polito (look for the last at the noir intersection of Hollywood and God, in Memphis, or even Chicago).

More usually known for her “transgressive” writing on sex, Gaitskill has written admiringly about The Confessions of Nat Turner, which many regard as “transgressive” itself, despite James Baldwin’s famous defense of the novel when ten black writers responded with a volume of protests a year after Styron published the novel: “He has begun the common history—ours.” That history, as well as Styron’s legacy, is appraised in cultural, literary, and personal terms in Andrew O’Hagan’s recent New York Review of Books essay/review “Styron's Choice,” which includes Alexandra Styron’s Reading My Father: A Memoir (Scribners’); Styron’s youngest child was four when her father’s most controversial work was published, and it provides her own book’s starting point. More to the point of this essay—language itself—and giving full and appropriate context for the origins of Baldwin’s defense, however, is a recent Examiner article by Aberjhani: it should be remembered that Baldwin, a preacher’s son, had ears  that rung with the cadences of the King James Bible no less than Styron’s own, or Dave Smith’s. Meaning that while one of the most common criticisms Styron received for his depiction of Nat is the “artificiality” of the interior speech/thoughts he gives the novel’s main character, how else would a man whose only interlocutor was God and whose ceaseless re-reading of the KJB, which Smith averred has provided the common tongue for generations of Southern blacks and whites alike, speak in the mind of a novelist who, like Smith himself, was steeped in Tidewater Virginia? Aberjhani, as astute a reader of Baldwin as O’Connor and Kafka, is obviously—and literally—attuned in this case: “virtually everything [Baldwin] wrote—whether essays in The Fire Next Time, short fiction in Going to Meet the Man, or the stories in novels like Go Tell it On the Mountain—was a form of poetry itself.”

that rung with the cadences of the King James Bible no less than Styron’s own, or Dave Smith’s. Meaning that while one of the most common criticisms Styron received for his depiction of Nat is the “artificiality” of the interior speech/thoughts he gives the novel’s main character, how else would a man whose only interlocutor was God and whose ceaseless re-reading of the KJB, which Smith averred has provided the common tongue for generations of Southern blacks and whites alike, speak in the mind of a novelist who, like Smith himself, was steeped in Tidewater Virginia? Aberjhani, as astute a reader of Baldwin as O’Connor and Kafka, is obviously—and literally—attuned in this case: “virtually everything [Baldwin] wrote—whether essays in The Fire Next Time, short fiction in Going to Meet the Man, or the stories in novels like Go Tell it On the Mountain—was a form of poetry itself.”

Gaitskill’s perspective on The Confessions comes from a slightly different slant but, considering the high esteem Barthelme has long accorded her, the exquisite intelligence of her remarks might have been predicted: like Baldwin, she doesn’t view The Confessions as an act of racial literary appropriation. Indeed, Gaitskill’s ultimate concerns lie with language and the truth of character as rendered through specific scenes.

Gaitskill’s perspective on The Confessions comes from a slightly different slant but, considering the high esteem Barthelme has long accorded her, the exquisite intelligence of her remarks might have been predicted: like Baldwin, she doesn’t view The Confessions as an act of racial literary appropriation. Indeed, Gaitskill’s ultimate concerns lie with language and the truth of character as rendered through specific scenes.

Of course Turner’s speech is “invented,” writes Gaitskill, or a translation of “nonverbal intelligence into language.” For, as she points out, even transcribed human dialogue sounds artificial when put on the page. “But,” she continues, “when I read it the emotional power of his invented language was real enough to make me cry for the misunderstood heroism of this man.” Heroism? Isn’t it a mindless meeting of rage and idealism melded with budding sexuality that causes Turner to murder the young woman who has unthinkingly befriended “one of the darkies” and expressed concern about their plight to him? No, Gaitskill adds: “you felt so much for both of them, and even though what he did was terrible, Styron made you understand why he did it, had to.”

4/19/12

100213 17:40